The measure of a translation’s faithfulness can conceptualized as a point on a continuum, with “literal” marking one end and “free” marking the other. At some imaginary balancing point somewhere in between exists the point marked “faithful”.

Personally, I have conceptualized that “faithful” spot as an ideal. The translator makes use of a specialized, unique set of language skills to render an author’s work in another language for another audience as though the writer had written it in that language and for that audience. That skills set no doubt includes creativity and ingenuity, of particular varieties. A translator who tampers with this process becomes a writer and ought for the sake of all involved to present original writing under his or her own name.

Jorge Luis Borges has argued differently, and Efrain Kristal has captured well his views in his book Invisible Work: Borges and Translation. According to Kristal, in what this blogger admiringly views as an ultimate crusade against ego, Borges went against the tide of popular protectiveness for the author, and opted to revere instead the work the author produced.

According to popular thought, a translation is inherently inferior to its original, because the author is not the translator, and cannot hope to carry over all the thoughts, feelings, ideas etc. that went into the original. Such a view, of course, elevates the author to the ranks of God, coherent and perfect, and puts the translator in a bind whenever an obvious mistake or an opportunity for improvement presents itself (whether these weaknesses could have been addressed in the original language or not).

Borges instead elevated the work itself, seeking after the well-being of the work and its quality, and saw translation as a medium for exposing the weaknesses of the original and offering a forum for improvement. He advocated for nourishing a work by breaking it down and building it up again rather than nourishing a writer’s ego by patting and cooing the writer whatever was done, good or bad.

True to his beliefs, Borges encouraged free translations of his own works, liking an English translation of Don Quijote more than the Spanish original. He was not the only major literary figure to put the text before the source, as it is reported that Gabriel Garcia Marquez liked Gregory Rabassa’s rendering of One Hundred Years of Solitude better than his own.

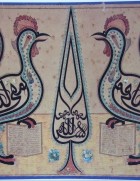

And in so doing, Borges and Garcia Marquez do not so much invent as reinvent. Copyright laws were not known in the Middle Ages, which is why certain well-known texts from that time such as The Book of 1,001 Nights and El Conde Lucanor are not so much a single text as a grouping of appropriations. If one did not have a particular fondness for all the stories in a manuscript, one was free to add, subtract, or change whatever elements one desired–in other words, to make what one perceived as improvements to it.

When we understand a translator’s work as a practical service for a practical purpose–if we think and operate on that level–then the conception of the importance of faithfulness in translation presented at the beginning of this post holds true. But when we understand translation as one tiny component of the processing of advancing civilization, of building a better, brighter, more insightful world–then it holds true that writers should release their egos and open their ideas to exploration, to conversation, to refinement, to improvement.